A stem-cell derived human embryo model showing blue cells (embryo), yellow cells (yolk sac) and pink cells (placenta).

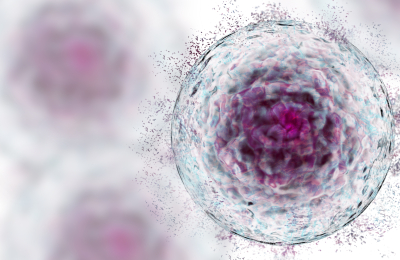

Scientists have grown an entity that closely resembles an early human embryo, without using sperm, eggs or a womb.

The Weizmann Institute team say their "embryo model", made using stem cells, looks like a textbook example of a real 14-day-old embryo.

It even released hormones that turned a pregnancy test positive in the lab.

The ambition for embryo models is to provide an ethical way of understanding the earliest moments of our lives.

The first weeks after a sperm fertilises an egg is a period of dramatic change - from a collection of indistinct cells to something that eventually becomes recognisable on a baby scan.

This crucial time is a major source of miscarriage and birth defects but poorly understood.

"It's a black box and that's not a cliche - our knowledge is very limited," Prof Jacob Hanna, from the Weizmann Institute of Science says.

Instead of a sperm and egg, the starting material was naive stem cells which were reprogrammed to gain the potential to become any type of tissue in the body.

Chemicals were then used to coax these stem cells into becoming four types of cell found in the earliest stages of the human embryo:

- epiblast cells, which become the embryo proper (or foetus)

- trophoblast cells, which become the placenta

- hypoblast cells, which become the supportive yolk sac

- extraembryonic mesoderm cells

A total of 120 of these cells were mixed in a precise ratio.

The hope is embryo models can help scientists explain how different types of cell emerge, witness the earliest steps in building the body's organs or understand inherited or genetic diseases.

Already, this study shows other parts of the embryo will not form unless the early placenta cells can surround it.

There is even talk of improving in vitro fertilisation (IVF) success rates by helping to understand why some embryos fail or using the models to test whether medicines are safe during pregnancy.

By James Gallagher, via BBC News. Read more - https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-66715669